Two newlyweds begin their honeymoon by stopping off in rural France to visit the bride’s cousins, only to discover en route that they have recently passed away. Continuing to the deceased’s decrepit castle to pay their respects, they are greeted by two servants and persuaded to stay the night, during which the bride is visited by a third woman and led out into the adjoining cemetery . . .

Le Frisson des Vampires, Rollin’s third feature, is far more accomplished than the preceding two and a far better introduction to the director’s work. This is due in no small part to the experience he had gained to that point, and may also reflect the influence of Monique Natan’s Les Films Moderne, the latter having a track-record of film production, even if the former – personally – did not. Rollin spoke subsequently of the additional resources he had at his disposal, including an actual dolly for the first time, which is put to use early on as the camera glides from the cold blue exterior of the castle to the apparent warmth of its interior. To be clear, we are still talking about a low budget film shot almost entirely on location with an inexperienced cast, but the production seems to have been far much more orderly this time around.

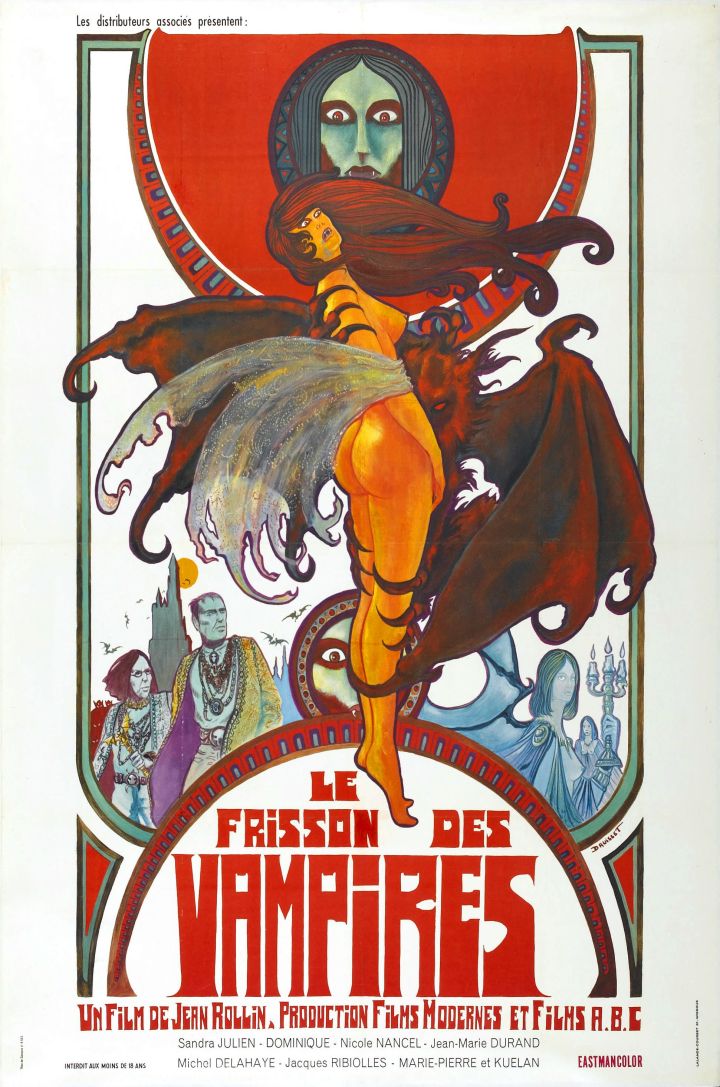

Essentially the story of a virgin falling under the influence of vampires, Rollin decided to pepper the screen with bizarre images and delivers some of the most memorable of his career. The first time Isle – our virgin – encounters Isolde – our (principal) vampire – the latter is climbing out of a grandfather clock, and the second time she bursts fourth from the drapes above a bed. Elsewhere we see a skull in a fish tank, a castle that bleeds as one of its occupants dies, and the beautiful Isle, now reluctant to face sunlight, holding a fallen dove to her mouth. Perhaps most striking of all is the sight of Isolde’s coffin on a sofa in the grounds of the castle, a direct reference to Magritte’s Madame Recamier. Incidentally, Isolde looks like a reference to a painting herself, or more accurately paintings, specifically those of Gustav Klimt, though I’ve never seen anything from Rollin to suggest this is deliberate.

“I am your friend. I have things to tell you, to explain to you, to show you.”

When people talk of Rollin it tends to be in these terms – the surreal imagery, the recurrent themes, perhaps the languid pacing – but watching the early films again, particularly this one, it’s worth noting how willing he was to experiment on a technical level. An obvious example can be found towards the end of the film, as Isle’s mysteriously-resurrected cousins circle her prone husband Antoine, the camera tracing their movements in one long pan around the room, while those on the peripherally literally cling to the walls. I’m not sure these flamboyant directorial decisions actually contribute much to the whole though, and think Rollin was most effective when using the camera more subtly, capturing images best left to speak for themselves. For instance, there is a sequence around the half hour mark, at the conclusion of the first (proper) scene with the dandy cousins, in which the camera withdraws as Isle and her husband Antoine leave the table, as the servants simultaneously enter the frame and take their places in front of the vampires, staring into space as their breasts are exposed. It may not be of great narrative significance (it was actually something of a joke, given the commercial requirement to bare female flesh) but it certainly leaves an impression.

Incidentally, one would ordinarily be reluctant to attribute the visual components of a film so readily to the director, but listening to Rollin does suggest these aspects were carried out to his instruction, based on his conception. He is (strictly speaking, was) quick to credit cinematographer Jean-Jacques Renon with regards to the film’s outlandish, Bava-esque lighting though, which is most prominent during the nighttime scenes, in which the cemetery is bathed in infernal reds.

On the subject of collaborators, we should also acknowledge the contributions of Michel Dellasalles, who provided a number of distinctive statues seen in the film, and the band ‘Acanthus’, whose prog-rock score may be the most memorable of any Rollin film. Apparently a group of students recommended to Rollin by mutual acquaintance Jean-Phillippe Delamarre, their work here calls to mind Goblin – well, a low-rent, garage Goblin – who scored numerous Italian horror films in the late seventies.

A prime example of Euro-cult / Euro-trash, it would be naive of me not to acknowledge that the film will appear amateurish, camp, even laughable to many viewers. In fairness, Rollin included elements of humour as a repost to those who had laughed at his earlier films, and that might be one of the reasons he accepted the wildly-theatrical performances of Michel Delahaye and Jacques Robiolles as the dandy vampires, resplendent in their earrings, frilly shirts and velvet trousers. The acting is strange across the board though. Sandra Julien, in her first film, is generally inexpressive as Isle, while Marie-Pierre Castel and Kuelan Herce, like their analogues in La Vampire Nue, could hardly be more blank as the servants. I’m not sure how much any of this matters though – it doesn’t matter to me – given the film’s fairy tale simplicity and general idiosyncrasy. That’s not to say performances are irrelevant in an eccentric, somewhat surreal vampire film, but we might want to calibrate accordingly. We might also want to keep in mind Rollin’s visual bent, his talent for conjuring memorable images, which is at the heart of his appeal and approach. We sense Isle’s affinity to the dead when we see her all in white, ghost-like in the cemetery at night, and we know she has fallen under the spell of the vampire when we see her naked, clinging to the clock from which she first emerged.

A critic might also argue that an erotic horror film should be either erotic and / or horrific, and Le Frisson is neither. The film’s original trailer could be cited as evidence in this context, given its nudity, it’s reference to monsters and a blood cult. That’s really just marketing though, and it’s not clear that Rollin was particularly interested in thrilling or chilling his audience. I would also be reluctant to criticise a film based on extrinsic, elusive factors such as audience expectations. Rollin’s film were obviously commercial undertakings and this informed their content to some degree, but forty-five years later their success or failure can only really be judged in artistic terms.

The conclusion of Le Frisson takes us back to the pebbled beach at Dieppe, to the scene in which the vampire queen inadvertently resurrected the dead in Le Viol du Vampire, and the ‘vampires’ of La Vampire Nue revealed themselves to be nothing of the sort. Here, distraught at what he’s seen, Antoine runs, firing bullets at the sun. It’s rally no surprise that Rollin’s films were greeted with derision at the time, given their bizarre imagery, strange air and disregard for genre conventions. Equally, it’s no surprise they’ve acquired cult status over time, for the very same reasons.

Notes:

WordPress does not lend itself to footnotes, but the following were consulted in constructing this review:

Immoral Tales, by Pete Tombes and Cathol Tohil (1994)

Virgins & Vampires, by Jean Rollin (1997)

Rollin’s essay and commentary track, which accompanied the Encore release of this film in Holland

Tim Lucas’ liner notes, which accompanied the Redemption release of the film in the US.