If I had been asked about my favourite filmmakers twenty years ago, the name Walerian Borowczyk would have featured prominently in my answer, which seems strange in hindsight, given how infrequently I’ve revisited his films in the intervening decades. A Polish illustrator turned animator who garnered considerable acclaim for his short films, the received wisdom is that he became mired in pornography shortly after switching to live action features, and his career suffered accordingly.

The turning point – or at least the point at which perception of his work began to shift – is Immoral Tales, a portmanteau comprising four sexually-themed shorts which was apparently suggested by Argos films’ Anatole Dauman in response to the relaxation of censorship around this time. I’m not sure that I would describe it as a great film (though it was a great commercial success) but it is a key Borowczyk film, one of the clearest examples of the style which was so striking to me then and which continues to attract admirers to this day.

Immoral Tales (1974)

I don’t think it’s helpful or accurate to describe Borowczyk as a pornographer, and I don’t intend to spend time presenting the case for or against. I think some of the criticisms often levelled at pornography are pertinent to Immoral Tales though, given the meagre narrative elements which serve to facilitate the sex. The first short – The Tide – features two cousins visiting the coast, whereby the older of the two persuades the younger to fellate him as the tide rises. In the second – Therese the Philosopher – a young woman late back from church is confined to a single room by her furious mother, wherein she masturbates with the cucumbers thrown after her. The third – Erzsebet Bathory – features lengthy scenes of nubiles showering prior to their slaughter, and the fourth – Lucrecia Borgia – centres on an incestuous ménage a trois in the papacy.

“Bewail your failures in self-denial.”

Structurally, three of the four shorts herein – the Bathory section being something of an exception – are not so very different to the loops one might have found in adult bookstores at the time. There is no real narrative, no real characterisation. Indeed, there’s very little dialogue in the film. Instead we have a simple set-up, a sexual act of some sort and that’s about it. Of course, such a reading does the film and its writer / director a considerable disservice, because Immoral Tales is a deeply idiosyncratic film, unmistakably the work of Borowczyk from the first frame to the last. It’s also frequently, extraordinarily beautiful.

Borowczyk’s training as an artist – he studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Krakow – is evident in all of his films, but rarely more so than here. It’s evident in the careful compositions, the set dressing, the obvious interest in objects, textures and tactile details. We may not know much about the characters who visit the coast, but we can almost feel the wetness of their shoes, the discomfort of the pebbles beneath their feet. We may not remember their names – I’m not even sure they’re given names – but we are unlikely to forget the images of his somewhat gnarly finger caressing her lips, penetrating her mouth, teasing her tongue.

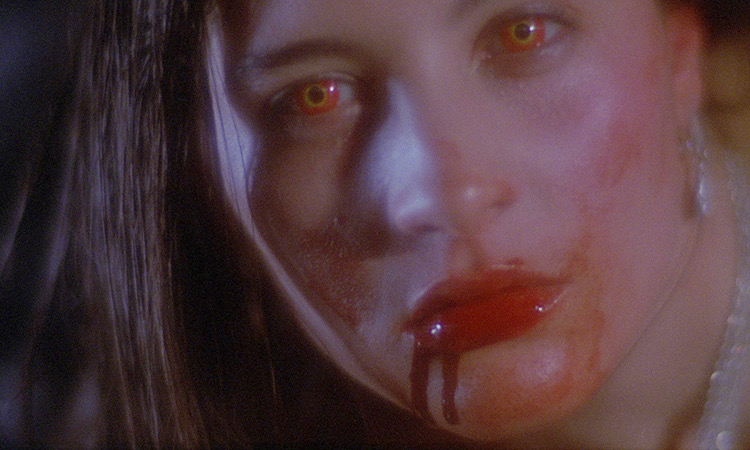

It’s images like this which make the film so compelling, like the blooming Therese stroking the pipes of the church organ, the naked nubiles lounging around Bathory’s bed, their viscous blood on her breasts thereafter. In Borowczyk’s world, aesthetics trump ideology. We should not assume it to be solely an exercise in style though, as two of the four ‘tales’ have anti-clerical undertones and two depict incestuous encounters. Immoral tales, indeed. If there is more to this than meets the eye, perhaps it’s the idea that lust will always find a way, regardless of the morality of the day.

The Beast (1975)

When Borowczyk screened a draft of Immoral Tales at a film festival in 1973 it contained a segment entitled ‘The True Story of the Beast of Gevaudan’, in which a young woman sets off into a forest in search of lost lamb, only to encounter a large, prodigiously endowed beast. Outrageous by any standards and tonally very different to anything in the eventual theatrical release, the segment was ultimately dropped and instead formed the basis of his next feature, his most famous feature.

“I like forests and animals.”

The Beast in its feature-length incarnation is apparently based on a novella by Prosper Merimee, in which a young man is suspected of having bestial characteristics due to his mother having been attacked by a bear while pregnant. In Borowczyk’s hands this premise assumes a somewhat absurd tone, as a Marquis and his inept accomplices hurry to arrange a marriage for his awkward, hirsute son, a marriage which will apparently save him from a terrible fate.

I remember being dumbfounded by The Beast on first viewing, at a film festival in the nineties, when it was still banned in Britain. I think I had been expecting something more sinister, certainly more serious, perhaps even something erotic. The Beast isn’t really any of these things though. It’s a slow burning drama that explodes into slapstick, a demented fairy tale that begins with footage of horses mating and ends – effectively – with a seemingly insatiable woman copulating with the titular beast. It’s a film that almost defies classification and has, to the best of my knowledge, no real precedent or antecedent.

The inherited footage appears here as a dream, which goes some way towards alleviating the marked tonal difference between it and the framing story. In a device reminiscent of the aforementioned Therese segment of Immoral Tales, the American heiress who travels to meet her betrothed becomes increasingly excited by the sights of the chateau, by the horses, the explicit drawings, the torn corset in a display case. It’s her dream that drives the film towards its conclusion and guaranteed its infamy.

If playing this sequence for laughs was intended to bemuse and befuddle the censorious – and I have no particular reason to believe it was – it didn’t work, as The Beast was cut and / or banned for years following its initial release. It does add immeasurably to the strangeness of the whole though. We get POV shots from both the predator and the prey here, including some as the latter rocks back and fourth in response to the thrusting of former. We also get shots which look like they’re lampooning more conventional pornography, as the aroused female licks her lips and teeth, rubs the beast’s copious ejaculate onto her breasts. It’s every bit as bizarre as it sounds.

One could be forgiven for wondering what the meaning of all this is, given the obvious thought that went into the production. Certainly unleashed human sexuality is presented as a destructive force here, more so than the pure animal instinct with which it’s contrasted. Perhaps Borowczyk was a fan of Freud?

***

It occurs to me that I haven’t referred to a single cast member by name thus far, and that might be illuminating. In Immoral Tales in particular, the cast are figures in a frame as much as anything, they could almost be referred to as models. Paloma Picasso, daughter of Pablo, does have a certain regal presence as Countess Bathory, and Charlotte Alexandra – Therese – is notable for having starred in Catherine Breillat’s debut a few years later. In The Beast, Lisbeth Hummel is suitably wide-eyed as the impressionable heiress and Guy Trejan – the Marquis – does a good job of keeping his head while all around him are losing theirs. Of course Sirpa Lane steals the show without saying a word, taking on the beast with gusto and ensuring exploitation immortality in so doing.

For all that, the actress most frequently associated with Borowczyk is not Sirpa Lane nor even Ligia Branice, star of Goto (1969) and Blanche (1971). It’s Marina Pierro, an Italian who somehow resembles the work of an old master made flesh, who appeared in five of the his later films, including his memorable adaptation of The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr Hyde.

The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Miss Osborne (1981)

It will surprise precisely no-one that Borowczyk’s reimagining of Stevenson’s classic text differs significantly from both the source and previous film adaptations. For a start, the action takes place over the course of one night and (more of less) in one location. More particularly, the film is built around a party to celebrate the engagement of Henry Jekyll and Fanny Osbourne, during which the guests find themselves by turns hunting for and hunted by the bestial Hyde. It’s the closest Borowczyk ever came to a straight horror film.

“All the beauty of evil.”

By introducing the titular Miss Osborne into proceedings Borowczyk took the audacious step of bringing a figure from Stevenson’s private life into his fictional world, and also afforded himself the opportunity to portray Hyde’s lust in ways the would be impossible in earlier, or indeed later adaptations. Here Hyde is not the shrunken figure of Stevenson’s novella but a sadist endowed with a monstrous member, a member with which he literally tears through Dr Jekyll’s women.

This probably sounds more scandalous than it actually is, because while the film is quite violent and features some nudity, it’s first and foremost a visual tour de force by the director and his accomplices, most notably cinematographer Noel Very. The cast seem to radiate light amid the darkness of Jekyll’s townhouse, and the contrast is heightened by shooting them from adjoining rooms, framing them within doorways or reflected in mirrors. As usual, the attention to detail is obvious, in the costumes, the appliances and artefacts of the era. Really, very few horror films are as beautiful to behold.

It’s hard to imagine anyone going into an adaptation of Jekyll and Hyde not knowing they are two sides of the same coin, but the transformation scenes remain crucial and Borowczyk’s are easily the most memorable I’ve seen, displaying craft and creativity. Rather than drinking the transformative liquid, he has the characters submerge themselves in it, most notably in a lengthy scene at the heart of the film in which Jekyll literally bathes in it, spasming wildly as Fanny looks on in horror. When he emerges from beneath the surface – larger, more muscular – he extols hatred and precedes to beat his own mother, ultimately stamping on and breaking one of her legs. It’s notable that following Fanny’s equally memorable transformation, she also attacks her mother, repeatedly stabbing her as the film builds to a crescendo. Again, one wonders if Borowczyk was a fan of Freud.

The intention had been for Udo Kier to play both Jekyll and Hyde, as Spencer Tracy, Christopher Lee and many others had done before him. Apparently Borowczyk was dissatisfied with the effect though, which is something of a mixed blessing. I’m not convinced Kier had the physical presence to play a sexual sadist, at least not in this context, and Gerard Zalcberg, who plays Hyde in his stead, looks much more menacing. He doesn’t look anything like Kier though, neither a regression from nor an evolution of, and for me that’s jarring.

Elsewhere Franco favourite Howard Vernon plays Lanyon and Patrick Magee – in his last screen role – steals several scenes as an aged General in full military regalia. Did I mention that Jekyll’s guests include a grotesque, aged General with a penchant for beating the bare buttocks of his daughter, and that Hyde hunts his prey with a bow and poison-tipped arrows? No?

My intention in writing this piece was to revisit and review films I had not seen in many years, not to write a career retrospective or assess the credentials of the director as an auteur. Some things are difficult to ignore though, and I’m not just talking about the director’s oft-acknowledged interest in antiquarian objects. It occurs to me that all three films feature representatives of the Catholic Church, and they range from ridiculous to repulsive. It also occurs to me that sex is a destructive force in Borowczyk’s world. Indeed, I’m struggling to think of single instance of consensual sex that reaches a satisfactory conclusion across the three films – and they contain a lot of sex. Perhaps the closest we come is the finale of Dr Jekyll, as the two ‘monsters’, freed from their inhibitions, flee the scene of their crimes in each other’s arms. Perhaps it’s not human sexuality that’s the problem, perhaps it’s the repression thereof.

***

WordPress does not lend itself to formal footnotes.

On reflection, there is an Italian film called The Beast in Space (Alfonso Brescia, 1980), in which Sirpa Lane apparently re-enacts her encounter with the beast . . . well, a beast.

Ligia Branice was actually Borowczyk’s wife, in addition to appearing in three of his features.

I appreciate that Jekyll and Hyde are so physically dissimilar in Stevenson’s novella that the former’s friends fail to recognise him in the latter. Perhaps I am just conditioned to expect one to look like a regression of the other, for one actor to play both roles.

Bibliography:

Immoral Tales, by Pete Tombs and Cathal Tohill (Primitive Press, 1994)