Funding for exploitation films was becoming increasingly hard to come by in France as the seventies wore on, which probably goes some way to explaining Franco’s problematic two-year association with Swiss producer Erwin C. Dietrich. The two apparently met around the time of Midnight Party (1975), for which Dietrich bought German and Italian distribution rights, after which Franco pitched directly and secured a deal for three films funded by Dietrich’s Elite Films, one of which was Barbed Wire Dolls (1975).

“They enjoy their torture, it’s an honour. The power of law is ours.”

A borderline-derelict women’s prison is ruled with an iron first by a brutal governess (Monica Swinn) and her similarly-sadistic doctor (Paul Muller). On their watch prisoners are starved, deprived of sleep and subjected to electroshock therapy. Oh yes, they’re also sexually abused. In narrative terms, that’s about it. Three of them try to escape.

I believe this was the first film Franco shot with Dietrich’s money and the Swiss was apparently horrified by the results – not necessarily by the content but by the ineptitude with which it was rendered. Shot near Antibes in the South of France, the cinematography is credited to ‘David Khune’, a pseudonym often used to disguise the contributions of the director himself. If that weren’t enough to give the game away, the incessant panning and zooming – not to mention the rather relaxed approach to focus – should leave us in no doubt as to who was behind the camera.

While the technical merits – or lack thereof – were alarming to the producer, the content of the film is likely to have raised eyebrows with audiences in the mid-seventies and remains rather shocking to this day. Not only is the film relentlessly brutal, the brutality is inflicted almost exclusively on women and begins with the very first scene, in which a bare-chested, whip-wielding Eric Falk verbally abuses and physically intimidates a naked, chained female. That this is done with the obvious approval – presumably even at the behest of – a female authority figure seems unlikely to assuage the concerns of those inclined to see misogyny in exploitation films of yesteryear.

There is intermittent talk of politics – of the regime being exposed by leftist writers and overthrown by revolutionaries – but it’s vey superficial. In Barbed Wire Dolls, the abuse of power is sexually rather than politically motivated. Swinn initiates sex with the beautiful Martine Stedil, initially – naturally – taking the dominant role, before imploring her presumably terrified prisoner to beat and degrade her. Muller is also seen having sex with one of the prisoners – Romay, if I recall correctly – and it’s a truly ghastly sight. Even the ultimate authority figure – ‘His Excellency’ (Roger Darton), who shudders with revulsion when touched by a naked prisoner – has a sexual interest in the outrages, instructing Falk to fuck her while he looks on.

“They like to play games with girls.”

For what it’s worth, I don’t think Franco was a misogynist. I think he was a commercial filmmaker with a taste for transgression, willingly working within genres which allowed him to explore the many facets of human sexuality. He could be – and of course, has been – accused of objectifying women and pandering to unhealthy desires though, and that is a difficult accusation to refute in this instance. Much of the director’s work can be seen as celebrating female sexuality but that’s a difficult case to argue here, given the coercion, the evident suffering, the absence – as far as I can remember – of anything that could really be considered consensual.

Leaving the violence to one side, the sexual activity herein will be problematic for some viewers – and presumably pleasing for others – not only because of the power dynamics at play but also the depiction, which is at times very graphic. Indeed the aforementioned encounters involving Swinn and Stedil, Falk and partner border on hardcore, containing acts which are clearly unsimulated.

In addition to the sex scenes, the film is packed with frontal nudity, with the inmates’ uniforms comprised of slightly oversized shirts and nothing more – literally nothing more. If there were any doubt about that last point we get plentiful shots of them laying around with their legs in the air, exposing, even stroking themselves. Only in the seventies . . .

Barbed Wire Dolls is not a good film by any meaningful measure. It’s not especially interesting narratively, has little to recommend it aesthetically, and as we said at the outset, is weak technically. Indeed it contains one of the most shockingly inept scenes I’ve ever seen in a professionally produced film, exploitation or otherwise.

We don’t get a lot of characterisation in any of these films, but Romay’s ‘Maria’ is at least afforded a little backstory here, courtesy of a dream sequence in which she – nude, obviously – is approached by her seemingly intoxicated father, played by the director himself. The ensuing, attempted incestuous attack is played out in slow-motion – literally. Presumably for reasons of budget, the camera actually captured this footage at full-speed, leaving Franco and Romay to to act in slow motion, albeit the pace of their movements ebb and flow, rarely falling in sync with one another. Really, it has to be seen to be believed.

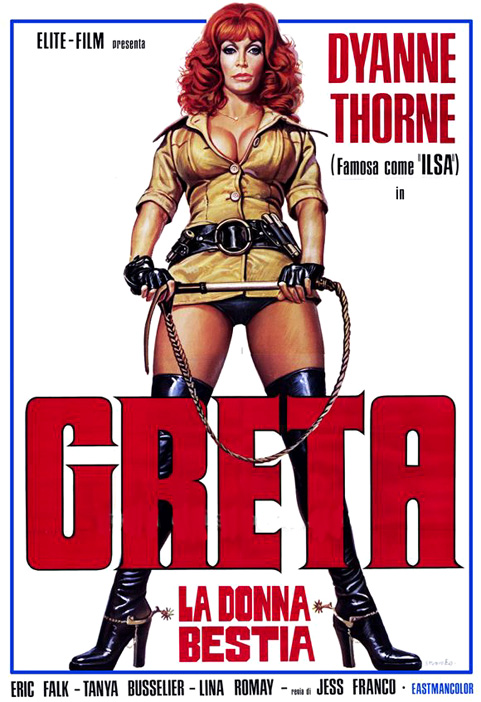

Despite Dietrich’s reservations – which apparently led him to question whether the film could even be released – Barbed Wire Dolls was a success at the box office and the pair returned to the well the following year with Greta the Mad Butcher (1976), in which a psychiatric hospital for women with sexual dysfunction in ruled with an iron fist by a brutal female (Dyanne Thorne) and her male accomplice (Eric Falk). A young woman (Tania Busselier) searching for her missing sister is falsely diagnosed in order to gain entry and establish what is actually going on within the institution.

“Do you know for what reason we’re here? We’re not demented or maniacs, we’re really political prisoners.”

Greta – or Wanda, or Ilsa – differs from its predecessor in some important respects. For a start, Dietrich was far more involved by this point – writing and producing – and he also installed an experienced technical team to work alongside the director. The cinematography was handled by Rudolf Kuttel, and there’s very little panning and zooming as a result. The lighting – courtesy of Hans Zweifel – also reveals far more care and attention. Indeed, the whole production reveals more care and attention, as is evident from the outset. The film begins with grimy footage of women showering collectively, intercut with Ms Thorne luxuriating in a bubble bath, immediately establishing the differing life experiences of (what we assume to be) inmates and (what we will come to learn is) their wicked warden. I’m not sure it’s art – well, one could argue all cinema is art, even if most of it is bad art – but it’s certainly more carefully constructed than anything in Barbed Wire Dolls.

It’s also notable that the sexual content is toned down here, which would probably sound like an astonishing statement to someone seeing the film in isolation. There’s no unsimulated sexual activity here though, and very few open-legged shots. The violence is ampped up in its place, which would probably sound like an astonishing statement to someone watching Barbed Wire Dolls in isolation. Among the ‘highlights’ we have Thorne embracing Romay, pushing pins deep into her flesh in so doing, performing some sort of genital torture on Busselier, she of the astonishing body hair, and suffocating a patient whose identity I won’t reveal here. That said, the film’s most shocking scene occurs when the uncharacteristically butch-looking Romay – having revealed she is suffering from the ‘trots’ – stands up from the toilet and instructs the aforementioned Busselier to lick her clean. In fairness, the latter is not depicted graphically and some of the former is handled more artfully than one might expect. Nevertheless . . .

To the extent that we can be objective about these things, Greta (Wanda, Ilsa) is a far better film than Barbed Wire Dolls. Indeed, it’s probably the best of the women in prison films Franco made for Dietrich. It’s technically accomplished, moves at a reasonable pace and is narratively coherent (in fairness they are all coherent, if a little threadbare). It also has Dyanne Thorne, who was – and remains – something of a name in exploitation cinema due to her titular roles in the infamous Ilsa films. It’s her presence which saw the film rebranded ‘Ilsa the Wicked Warden’ during the VHS era, prior to which it was also released as Wanda the Wicked Warden.

While Thorne undeniably has presence, her character does not have a lot of depth. Neither does Eric Falk’s, though we know he’s motivated – to a greater or lesser degree – by money because we see him filming the atrocities and selling the footage on the black market. I suppose Thorne is motivated by power and pursuit of pleasure – like her predecessor the monocled Monika Swinn – and perhaps that’s enough. I don’t think she ever really articulates that though. Unlike Jack Taylor and Maria Rohm in the first Eugenie (1969) or Paul Muller and Soledad Miranda in the second (1970), she’s a butcher rather than a philosopher, a sadist rather than a Sadean.

“What can they know about sex? What can a man know?”

The motivation of those in power is crystal clear in Love Camp (1977), if not entirely convincing. Built of a wafer-thin premise in which women are kidnapped and forced to work in a brothel servicing the ‘heroes of the revolution’, this is much more conventional exploitation fare. There’s some whipping here and boot licking there but nothing approaching the barbarism of the other films. It’s also – coincidentally or otherwise – the least memorable of the quartet.

I’d struggle to relay much more about the narrative because it’s really nothing more than a framework, again provided by Dietrich. We have no idea who the revolutionaries are fighting or why and we know nothing (of significance) about the prisoner / prostitutes, the majority of whom are not even afforded names. There is some rivalry and fighting between them – unusually, there’s also rivalry and fighting between those in positions of power, between the lesbian commandant and one of the key military men, both of whom fall under the spell of Ada Tauler’s ‘Angela’ – but it’s really all very flimsy.

The film doesn’t have a lot going for it in cinematic terms either, with the eccentricities of the director presumably constrained by the hand of the producer and / or presence of his technical team (Kuttel, Zweifel and co). All of these films are punctuated with shots which betray Franco’s fondness of exotic locations, but that aside, one wonders how different Love Camp looks to the WIP films Dietrich himself directed during this period.

With little to recommend it ideologically or aesthetically, one can only assume the sight of relatively attractive women – and really very unattractive men – showering in groups was enough to appease audiences in 1977, or maybe not, because Women in Cellblock 9 (1977) is a return to the barbarism of the first two films in this unofficial quartet.

“Bring the young girl, the pretty one. We must have the doctor examine her.”

Franco’s final foray behind prison walls – at least during this phase of his career – is arguably the purest of the four, and I realise that’s dangerously close to be an oxymoron. Here we have four women with no real identities falling into the hands of a brutal governess (Dora Doll) and her sadistic male accomplice (Howard Vernon) – stop me if you’ve heard this one before.

The first hour of so of Women in Cellblock 9 is built around four set pieces in which our protagonists – if it’s meaningful to refer to them in such a a way – are (individually) humiliated and tortured, with the latter centring on their genitals as often as not. Wholesome entertainment for all the family, this most certainly is not.

Appalling as this doubtless sounds, the film is not without merit. Dora Doll and Howard Vernon are, for me, the most convincing sadists in the Dietrich films, and the scene in which they abuse Susan Hemingway is among the most memorable. We see the latter alone in the first instance, begging for water while our sadists dine in an adjacent room, drinking champagne and listening to classical music. Having been brought before them, she is instructed to quench her thirst by performing cunnilingus on her chief tormentor, much to the delight of the leering, unshaven Vernon. Indeed it is he who enacts the final indignity, pouring salt into a glass of champagne before handing it to the desperate, naked girl.

This is strong stuff, and totally lacking the camp one might be able to find – I stress might – in the bare-chested Eric Falk, the monocled Monica Swinn or the abundant Dyanne Thorne. In fact, the aesthetics and power dynamics of the scene with Doll, Vernon and Hemingway called to mind Pasolini’s Salo (1975), which is not a film I ever thought I would liken one of Franco’s to.

To be clear, this is not a great film – it’s not even a great Franco film, if that makes any sense. There are signs the director was more engaged here than elsewhere though, in the performances of the sadists, the realisation of the set-pieces and the haunting, final image in which the camera seems drawn to but unable to make sense of sunlight breaking through the branches of a tree. Actually, for a film featuring so much ugliness, there are a number of striking images herein, such as when our three naked escapees rise from the banks of a lake, their image perfectly reflected within it.

“I never really believed that humans could be so cruel to each other.”

I’ve never really warmed to the Dietrich films, and revisiting this sub-set has done little to cause me to reevaluate. It’s not the nihilism that bothers me, though two of the four have particularly nihilistic endings. It’s not the content either – these are low budget films from another time and place, relics of a bygone era. It’s not even the flimsy narratives, because some of Franco’s finest films are pretty flimsy when looked at purely in those terms. I think the real problem is that they seem so workmanlike, so lacking in personality.

It’s tempting to blame Dietrich for this, either directly or indirectly; to assume he kept Franco on a tight leash, or simply hamstrung him with crews which straightjacketd or working conditions which stifled him. This doesn’t explain the flatness of Barbed Wire Dolls though, which seems to have been made with little to no outside interference.

Of course, an alternative reading is possible. The last three films discussed herein – if we leave the content to one side – are far more conventional than many that preceded them, and thus might be more approachable to viewers who would otherwise by put-off by the peculiar pacing, narrative sojourns and surrealism. Those are the things – or at least, those are among the things – that draw us to Franco though, that remind us we are in the hands of an auteur, however erratic. Without them, the films just don’t stimulate the senses in the same way.

***

WordPress does not lend itself to formal footnotes:

The three principle elements of Barbed Wire Dolls are nudity, sadism and smoking. Indeed, one of the prisoners even masturbates with a lit cigarette.

It’s notable that Wanda (Greta, Ilsa) also ends with a juxtaposition demonstrating the changed relationship between the patients and their tormentor.

Whatever aesthetic similarities there may be between Love Camp and Dietrich’s women in prison films, I doubt anyone masturbates with a cigar in Caged Women (1980), as Monica Swinn does here.

The closing shot of Women in Cellblock 9 recalls the conclusion of Antonioni’s brilliant L’eclisse (1962), though I doubt it was deliberate. Franco was not an admirer of the great Italian.

The fact that I can complete a 2,500 word essay on these films without referring to the scores is evidence in itself that they lack many of the hallmarks one associates with Franco.

Bibliography:

Immoral Tales, by Pete Tombs and Cathal Tohill (Primitive Press, 1994)

Bizarre Sinema!, by Carlos Aguilar (Glittering Images, 1999)

Flowers of Perversion, by Stephen Thrower (Strange Attractor Press, 2018)